Everywhere you look, right-wing fascism is on the march. Demagogues rule some of the most powerful nations in the world. At home, we have Trump, supported by an extremist right-wing party. In Brazil, we see Bolsonaro, who won election through a subterfuge, a corrupt alliance with a judge who imprisoned his opponent, Lula. In China, Xi Jinping appears to have cleared the stage to remain President for life and reverse whatever small measure of political freedom ordinary Chinese people had gained. In the UK, the racist toff Boris Johnson ambles about 10 Downing Street.

And in India where I spent my childhood, the HIndu supremacist Sangh Parivar rules the center unchallenged, with its political wing, the BJP in full control of Parliament. Like all right-wing governments, the BJP and Modi have opted to make a minority the target for their discriminatory politics. In India, the most convenient minority is the Muslim population, and the highest pay-off for a politician bent on sowing divisions is to focus on Kashmir.

“Gar firdaus bar-rue zamin ast, hami asto, hamin asto, hamin ast.”

If there is a Paradise on this earth, it is here, it is here, it is here.

— attributed to Jahangir

It’s the kind of treacle you’d find in a travel brochure. In fact, every travel brochure ever published about Kashmir incorporates this line. Here’s the thing though, Jehangir got it right.

Kashmir is a vast paradise of sublimely beautiful valleys, imposing mountains and breathtaking gorges. Its pastures are bejeweled with the sparkle of wildflowers and the radiance of rushing streams. Its high peaks and glaciers pierce a sky that is the clearest blue. At night, in the high valleys, it feels as if the stars are close enough to touch.

I am fortunate enough to have traveled our planet and have set foot on many of its most beautiful mountain ranges. The trip to Pehalgam, Srinagar, Jammu and Gulmarg I took more than three decades ago as a child, remains a vivid highlight of my travels. Since that somewhat peaceful interlude in the 80s, Kashmir has seen waves of protests and insurgency, and an unrelenting military response by the Indian government.

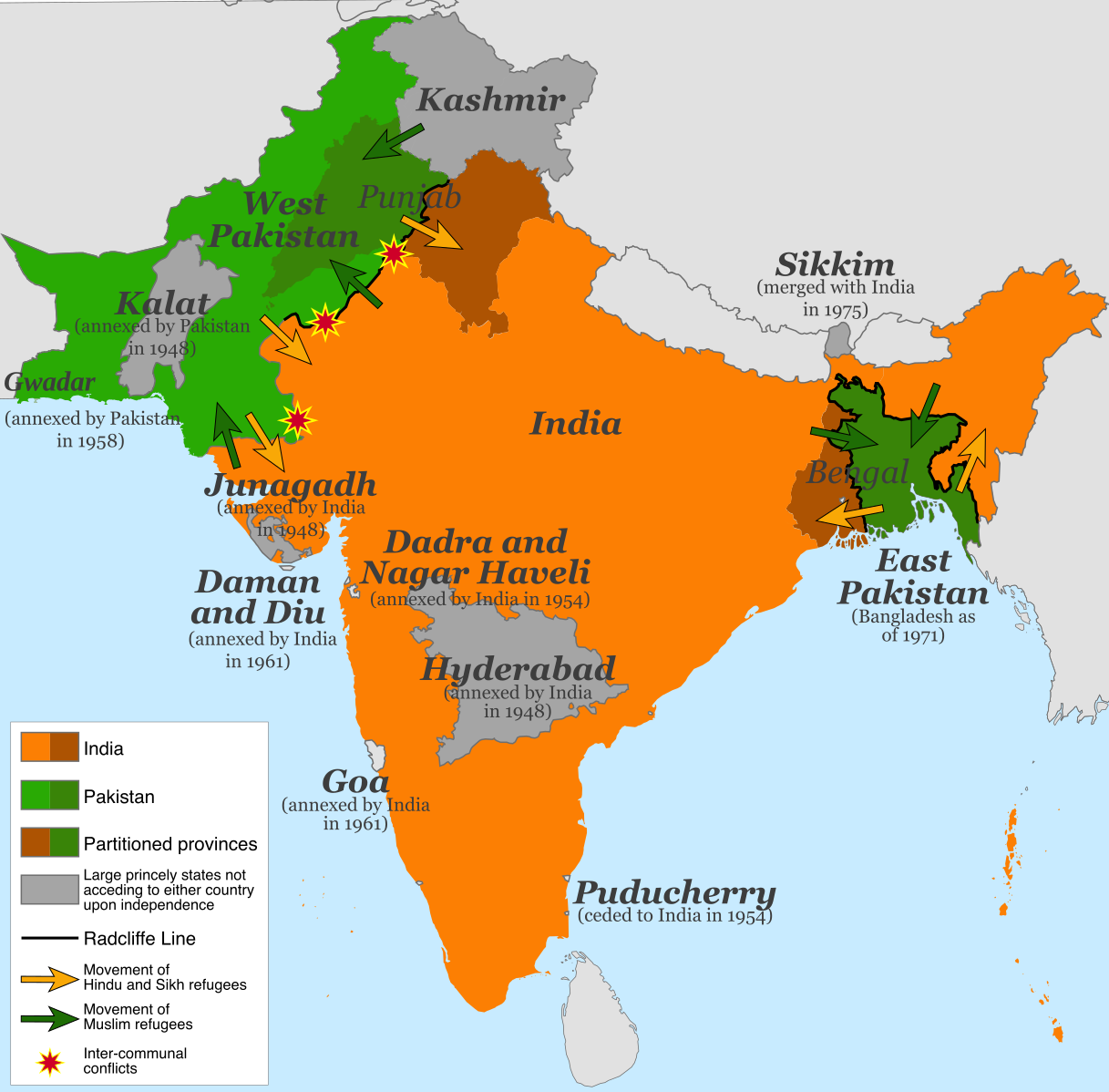

When the British left India in 1947, exhausted by World War II, Kashmir was a “princely state”, led by a monarch who had allied with the British empire. In the land grab and ethnic cleansing that accompanied the partition of the Indian sub-continent into India and Pakistan, Kashmir was unexpectedly partitioned as well, with one segment annexed by Pakistan. The green valley of Jammu and Kashmir, and the startling moonscape that is Ladakh were annexed by India. Ordinary Kashmiris never had a say in the matter, just as so many millions across India and Pakistan and what is now Bangladesh weren’t asked whether they wished for their homes to become part of this or that country.

In the ensuing decades, most of the border regions have accepted their fate as part of either an India or Pakistan. There are exceptions. The exploitative actions of the ruling classes in India and Pakistan or ethnic fault-lines have occasionally sparked separatist movements. Punjab saw a long-running insurgency for independence in the 80s and 90s, in the mountains of north-eastern India the Indian state’s repressive policies have fueled a decade long insurgency, in Baluchistan a similar dynamic has been playing out in reaction to the high-handed rule of the ruling Pakistani elite.

The real-politik at play in all these regional conflicts is the same. The population centers and powers that lie along the major rivers/plains seek to to control their drainage area and sources and create protective buffer zones by annexing the abutting, vast, empty areas. This is true of the powers that arise along the Indus in Pakistan, the Ganges in India, and the Yangtze and Huang in China. The people who live in places like Kashmir or Tibet or Xinjiang don’t have the numbers to resist.

Of all the post-1947 border questions, Kashmir has remained pre-eminent. Several wars have been fought over and in the region. China controls two small section high in the north, Shaksgam and Aksai Chin which in 1947 were part of the princely state called Kashmir. Pakistan controls Gilgit, Baltistan and a narrow strip along the Western edge of the former princely state.

12 million people live in Indian administered Kashmir, the majority of them are Muslim. All of them are Indian citizens, but for decades they have enjoyed a degree of autonomy as a recognition that the accession of Kashmir into India did not follow the clearer route of most of the other citizens. Kashmir has had largely its own legal code, and only Kashmiris were allowed to purchase land.

Then, two weeks ago, the Indian government led by the right-wing Hindu-nationalist Modi, suddenly evacuated Kashmir of all tourists, claiming there was a threat of terrorism. A day later the central government in Delhi announced it was dividing the state of Kashmir into two “Union Territories” that would be directly administered from Delhi. The central government also revoked the special autonomy granted to Kashmir and Kashmiris.

Several Indian legal scholars believe such changes, made without consulting Kashmir’s elected state government are unconstitutional. But Modi shares with Trump a taste for such legal battles.

Modi’s government is also engaged in a “citizenship review” at another end of the country. During the Bangladesh War of Independence in 1971, some indeterminate number of refugees entered India, and some have remained. Most prior Indian governments have paid no attention to any such refugees, who are largely integrated into Indian society. In any case, there are few social, cultural or linguistic differences between the people of Bangladesh and the people who live in the Indian states of Assam and West Bengal. And merely 24 years prior to 1971, all these people lived in the same country.

Now, 48 years after 1971, the BJP led government is using the pretext of 1971 refugees to question the citizenship of vast numbers of Muslims living in the region. Their aim in Assam is quite plainly to strip millions of Muslims of Indian citizenship. As part of this campaign, the government seems to have started creating vast detention camps. Perhaps the idea for the camps comes from Trump, or from the camps China has created to incarcerate millions of ethnic Uighurs. The language being used by Modi’s party to describe Muslims in Assam is frighteningly reminiscent of rhetoric that has accompanied gross human rights violations.

The head of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s ruling Hindu nationalist party took his invective against illegal Muslim immigrants to a new level this week as the general election kicked off, promising to throw them into the Bay of Bengal.

Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) President Amit Shah referred to such illegal immigrants as “termites”, a description he also used last September, when he drew condemnation from rights groups. The U.S. State Department also noted the remark in its annual human rights report.

“Infiltrators are like termites in the soil of Bengal,” Shah said on Thursday at a rally in West Bengal, as voting in India’s 39-day general election started. — www.reuters.com/…

Engage in any political conversation on open social media and you will soon notice numerous BJP supporters echoing Mr. Shah’s language, referring to the Muslim population as “termites”.

“Termites” don’t have rights that human beings respect. And so it goes with Kashmir under BJP rule. The central government has placed all politicians under house arrest, and put the entire state under a curfew, closing all schools, universities and businesses. Kashmir isn’t even a state anymore, it has been broken into two pieces, neither of which is a state, they will both be administered as union territories by the central government.

How did it come to this? Well, it’s been a long road. Over the past few decades, the Indian government, under both left and right-wing governments has eroded the rights of Kashmiri citizens. Under the guise of fighting an insurgency, Delhi has tolerated widespread and severe human rights abuses by security forces who have turned Kashmir into what can only be termed a decades-long military occupation. Rape, maiming, torture, this has all been swept under the rug.

Kashmir’s industries have withered under the draconian military presence, and its people have been impoverished. After decades of declining relative income, Delhi has decided to open the floodgates to non-Kashmiri investors. It is likely that most of the most attractive Kashmiri real property will now be snapped up by India’s upper crust. Gentrification in the Himalayas.

We cannot lay all the blame on the right-wing extremists who currently occupy the Indian parliament. Prior Indian governments, including the center-left Congress party, presided over the deterioration of rights in Kashmir. So in a sense this is the culmination of a process that has been underway for a while. But what has just happened feels different.

It’s worth noting that many of the attacks on minorities and fundamental human rights we’re seeing across the world are a direct result of the rise of a trans-national right-wing movement. It’s not accidental that while immigrants and minorities are being persecuted with fresh zeal across the US, indigenous rights are being trampled in Brazil, a campaign to imprison millions of Uighurs is underway in China, immigrants are demonized in Eastern Europe, and religion, caste out-groups are being persecuted in India. This is a global threat to the rights of minorities and the concept of integrated societies with equal rights for all. Many of the governments that would be more circumspect about their human rights abuses are more blatant today because of what they see the Trump administration doing or not.

There are also long-running domestic trends at play in India. The BJP is in the position it is because the Congress party has atrophied by perusing a policy of dynastic succession, reserving the top positions for the Nehru-Gandhi family while kneecapping every other talented politicians, and hewing to old ideas about campaigns, platforms and organization. Many promising politicians flee Congress to form their own regional off-shoots, balkanizing the left in India. It has not helped that the Nehru’s great-grandchildren appear completely removes from the cares of ordinary Indians, married to multi-millionaires and having enjoyed perks that most ordinary Indians cannot aspire to. Modi meanwhile, presents himself as a tea-stall worker who has done well, which is true. Though he’s also been known to accept the occasional gift of a $20,000 suit.

That trajectory contains a lesson for US as well. Not only for the Democratic party, which should avoid becoming as sclerotic as Congress is, but also for the rest of us. Modi is far more dangerous than Trump is, partly because he’s actually somewhat effective. If a Tom Cotton were to follow Trump, he might do far more damage.

— @subirgrewal